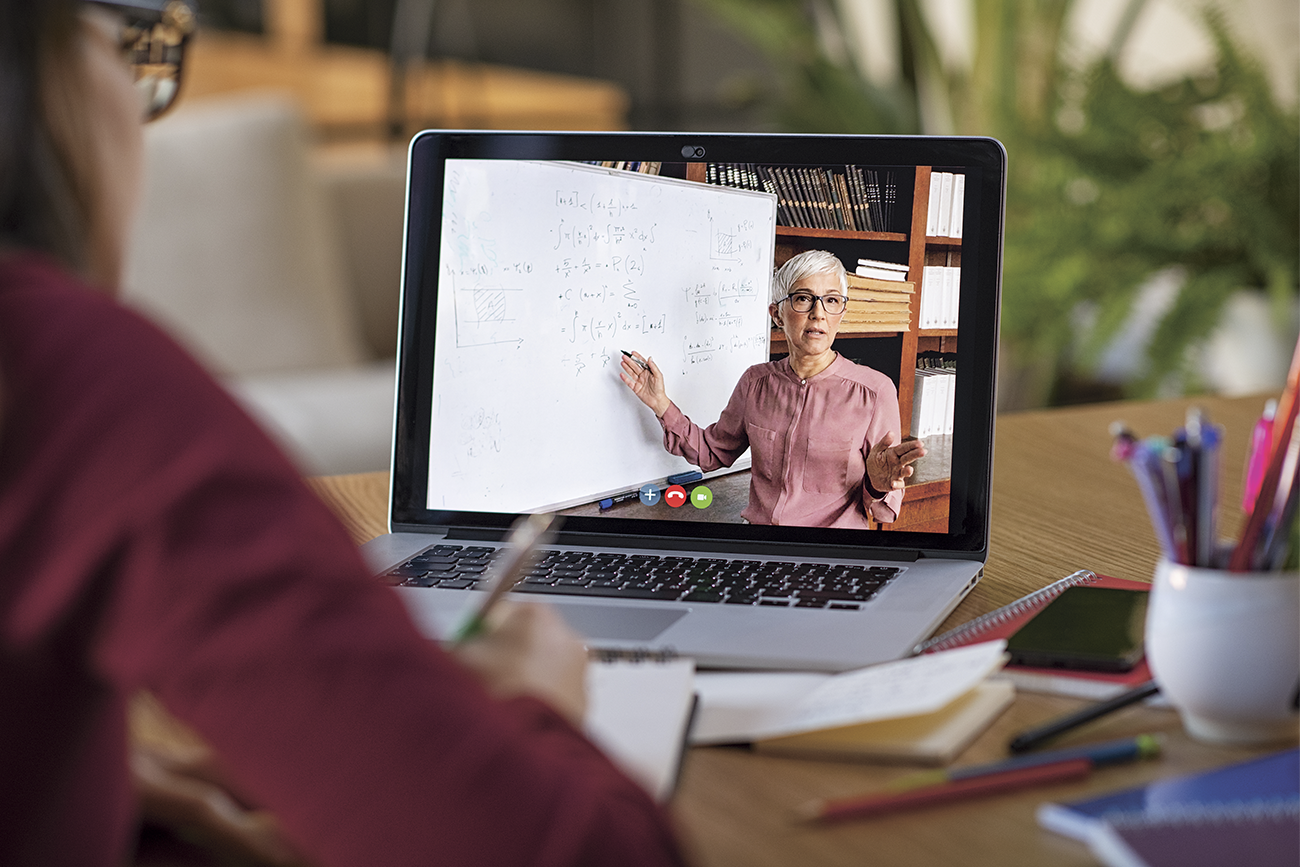

It all went by very fast. One day students were in class, the next one, campuses were closed and academic staff had to move their teaching online to save the semester for their students. But what was done in an effort of solidarity cannot be the new normal, warn academics.

“What we did was emergency remote teaching. This is not usual. This is not online teaching. We had to salvage weeks 10 to 12 and this is what we did,” explains Ian Milligan, associate professor in history at the University of Waterloo.

Milligan says that the development of an online course usually takes 12 to 18 months. In order to do a proper job, academic staff would normally get one or two course releases to develop the content and pedagogy, and would count on specialized staff at the university, such as IT technicians, to assist.

“We had extraordinary circumstances and our members stepped up in solidarity because we wanted to be part of the solution, but we are opposed to a unilateral implementation of online teaching,” says Caroline Quesnel, president of the Fédération nationale des enseignantes et des enseignants du Québec (FNEEQ), a union representing 34,000 college instructors and 12,000 contract academics in 13 universities.

This echoes CAUT's position. “While associations should be flexible given the seriousness of the pandemic, they should negotiate protocols for online instruction with their administration as collective agreement rights may be affected,” says CAUT Executive Director David Robinson.

“The agreement should specify that all measures taken in response to the COVID-19 crisis are temporary and solely in response to an extraordinary situation” adds Robinson. “Letters of Understanding to address that issue should specify which elements of the collective agreement continue to apply, and which are modified or suspended.”

Stephanie Ross, Director of the School of Labour Studies at McMaster University, notes that the rapid introduction of online teaching has increased inequalities amongst academic staff. “Certain people can navigate better than others. It is like inviting people into your home. Not everybody has the same level of social intelligence needed to be at ease and productive.

George Veletsianos is the Canada Research Chair in Innovative Learning and Technology and is a professor in the School of Education and Technology at Royal Roads University. He says that while online learning has been growing in Canada for years, what happened to the academic community in mid-March was dramatic and the transition for many was abrupt and difficult.

“Not only was it a big professional change, but it coincided with big changes in people’s daily routine. It left many faculty feeling grief and loss”, notes Veletsianos. He adds that when American faculty were surveyed at US institutions, many described that, apart from having to be more flexible, they also had to lower their expectations of students, which translated into fewer assignments and exams.

Teaching online also brings questions about intellectual property and fair dealing. “For at least the immediate future, online course delivery will be the standard. Fair dealing warrants an exceptionally broad interpretation in the current environment. There is a strong benefit to the public in providing online courses,” argues Sam Trosow a law professor at Western University.

That said, Trosow is worried about the online platforms and systems universities are requiring academic staff to use for their teaching. “I am not in control and I am forced to use a tool that I chose not to use and that has the capability to track what I am doing. I have huge concerns now that there are copies of what we do online, and this could turn into a real threat to academic freedom.”

George Veletsianos thinks that faculty and staff have to engage in advocacy and resistance. “We have to use the work of experts to explain to the administrators the implications of the technologies and products used in online teaching, because we are letting them into our classrooms.”