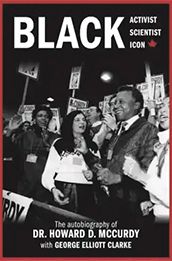

The Autobiography of Dr. Howard D. McCurdy

Howard Douglas McCurdy, George Elliott Clarke

Nimbus Publishing Limited, 2023; 324 pp;

By Titilola Aiyegbusi

“Canadians do a lousy job of remembering Black Canadians,” George Elliott Clarke maintains in the preface to Dr. Howard Douglas McCurdy’s Black Activist, Black Scientist, Black Icon. This appears to be a key motivation for McCurdy’s autobiography: to provide evidence of the history of Black people’s struggles in Canada while also taking stock of their contributions to nation building.

Posthumously published via George Elliott Clarke’s editorial assistance, McCurdy’s compelling narrative of Black political activism in Canada is one of survival and triumph, even in the face of the harsh realities of Canadian racism.

It is a captivating narrative, written in exquisite diction. With skillful use of literary techniques, McCurdy walks us through the complex realities of being: 1) Black, 2) Canadian and 3) excellent. These three attributes, McCurdy advises, are not normally considered to be compatible. The dynamics and systems in Canada make it impossible to embody all three simultaneously — a fact McCurdy soon realized as a junior high school student when he alone of his track team was refused dining services in a Chatham hotel due to racial segregation. But these facets of identity were triune in McCurdy, propelling him to be a trailblazer in all that he did, so that he won appointments to both the Order of Canada and the Order of Ontario.

In 21 chapters spread over 312 pages of text and pictures, McCurdy narrates his personal inheritance and the vital influence of his cultural heritage. He traces his lineage back to fugitive slaves from Kentucky and ex-slaves who arrived in Canada via the Underground Railroad. To understand the various stages of his life, and how each contributes to his overall experience, it is useful to consider the book in three sections: the tensions that shape the mature McCurdy (chapters 1-5), his pursuit of excellence in various callings (chapters 6-19), and reflections on the exit of the elder statesman (chapters 20-21).

Chapters 1-5 detail stories of growing up in London, Ontario. We follow the complex experiences of a boy who started life believing that to be coloured in Canada is no different from being white, to one who not only experienced segregation, but strove against its barriers by aiming to outrun, out-jump and outbest his peers. In his very early childhood, to be Black didn’t signal much other than that his curly hair could sometimes be an irritant: It was a magnet for white folks who too often felt compelled to touch it. The events captured in this section lay the foundation for the development of the character of the adult McCurdy that we encounter subsequently.

In chapters 6-19, we witness a McCurdy who has come to terms with the paradoxes of his youth and made the decision to chart his path through academia and subsequently, politics. In 1959, he became a lecturer at Assumption University, Windsor, becoming the first Black Canadian to secure a tenure-track position in a Canadian university. Fifteen years later, he became the first Black chair of any university department in Canada.

After 20 years in the classroom and the biology lab (during which time he served as president of the Canadian Association of University Teachers and founder of the National Black Coalition of Canada), and having been in 1961 a founding member of the NDP, which he helped name, McCurdy transitioned from academia into politics. He won a seat at Windsor Council as Alderman for Ward 3 in 1980 and would later represent the WindsorWalkerville riding in Parliament as an MP from 1984 to 1993. In his words, he became “the first New Democrat to be federally elected in Windsor and the first descendant of the Underground Railroad fugitive ex-slaves to sit in the Parliament of Canada.”

McCurdy’s years as a politician are eventful. He narrates many important debates, including the debate that condemned China for the 1989 Tiananmen Square protest. Other highlights include shaking hands with Pope John Paul II, meeting with Nelson Mandela, and sipping tea with the Dalai Lama. It is through his account that we glimpse the political landscape of Canada from the 1960s to the 1990s. This makes his autobiography a reference document for a de facto pan-Africanist and/or socialist critique of Canada’s positions on both global affairs and domestic issues.

The last two chapters capture McCurdy’s final years in, and exit from, politics. He presents, with august clarity, his thoughts on the events that would invariably dub him persona non-grata in certain political and media circles. While many of the incidents he recounts are sobering, they pale in comparison to some of the personal insults and physical abuse he endured during this time. For instance, while speaking during a question period in the Commons, a Tory MP shouted, “Shut up, Sambo!”. Also, in 2006, on his way home to Windsor from Detroit, he became the target of racist Canadian border officers at the Ambassador Bridge checkpoint, who threw him to the ground, cuffed him and put him in a cell. He was later charged with resisting arrest and obstructing a peace officer. Lacking any merits, the bogus charges were dropped as soon as the case went to court.

But the effect of the assault lingered, and it will continue to do so in the consciousness of Canadians who remember this incident and those who will read about it in this book. That a distinguished citizen in his seventies could be manhandled in such a manner without reasonable cause is heartbreaking, and even harder to swallow given his public profile as an elder statesman. Invariably, McCurdy’s narrative makes evident a sad truth: antiBlack racism in Canada is no respecter of age or status.

From a critical stance on style, petty nuisances such as his excessive use of the expression “lookit” were an unwelcome but minor distraction to good reading flow. One could argue, however, that such interjections capture the excitement McCurdy must have felt while remembering and writing about signal events. Although the book is generally an easy read and follows a reasonable and predictable sequence, there are moments in which McCurdy narrates events in such rapid succession that little room is left to digest the insights he shares from those experiences.

Undoubtedly, McCurdy’s life story points to the resilience of a man who would not cower in the face of racism and would stand tall, or even taller, among peers, upholding always that which is fair, right and true. To conclude his narrative, he offers instructive life lessons for how Black experience in Canada today should be understood:

My children experienced less racism than I, even as I experienced less than my progenitors. My grandchildren with their multicultural friends are hardly conscious of it at all. Yet, I do fear they lack the armament they may need versus the vestiges of racism they may yet face. They need to know the history of our struggle. Not knowing, they may be tempted to believe that there has been no change—or be frustrated by what has not changed. It is from an awareness of the past that they can best meet the need to change what yet needs to be changed.

McCurdy’s autobiography belongs in our classrooms, libraries and personal bookshelves. His narrative adds to our collective records and understanding of the history of Canadian politics. It also serves as a resource for researchers working on improving our understanding of Black experience in Canada. And to the literary critic, it raises questions about the term autobiography, asking that we re-examine its definition. For instance, how should we read life narratives edited by people who are separate from the autobiographer?

Importantly, McCurdy’s book is a must-read for Black Canadians, especially those who continue to excel and thrive in spaces that were predicated on their exclusion. Through this book, he reminds them that they have a forerunner to be proud of: His name is Dr. Howard Douglas McCurdy!

Titilola Aiyegbusi is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at the University of Toronto.